Richard J. Davidson : "Meditation Meets Science"

The excerpt found here offers -- along with the story of the beginnings, in 1986, of the Mind & Life Dialogs -- a description of the crucial and definitive 1992 events which initiated the Compassion Renaissance.

***

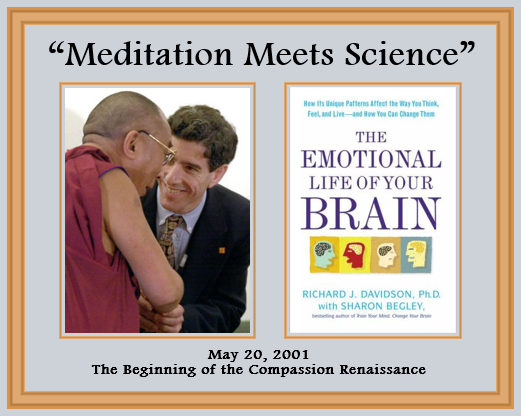

Richard J. Davidson & Sharon Begley, The Emotional Life of Your Brain: How Its Unique Patterns Affect the Way You Think, Feel, and Live -- and How You Can Change Them, 2012, Section "Meditation Meets Science," pages 183-190.

~ Meditation Meets Science ~

Back at Harvard, in what was now the beginning of my third year in graduate school, I therefore began to do a little research on meditation, in one experiment, Dan Goleman and I studied fifty-eight people who had varying degrees of experience of experience with meditation, from none at all to more than two years' worth. We administered some standard psychological questionnaires to them and found -- drum roll, please -- that more experience meditating was associated with less anxiety and greater attentional ability. We acknowledged that the difference might reflect different predispositions on the part of nonmediators, novices and experts -- that is, that being able to focus and having little anxiety might enable someone to stick with meditation for two years, whereas being a neurotic, fidgety type would have seemed awfully naive. Although I was thrilled that the paper was accepted by the Journal of Abnormal Psychology, publication was on guarantee of respect. When I told one of my professors about this work, he replied, "Richie, if you wish to have a successful career in science, this is not a very good way to begin."

The disdain of mainstream psychology was only none of the factors that made research on meditation less than desirable. The biggest impediment was that brain imaging had not been invented yet. The fairly crude EEGs that we used could detect electrical activity in regions of the cortex near the surface, where the electrodes were pasted, but no deeper. this meant that the vast majority of the living brain was opaque to science, including subcortical regions, which are so important for emotion. In the long run, though, not being able to study meditation scientifically in the1970s turned out to be a blessing in disguise. it enabled me to turn my full attention to the study of emotion and the brain; which ultimately led to the development of affective neuroscience as we know it today. and by the time i was ready to study meditation, the neuroscientific tools were up to the task.

Although meditation would not be part of my scientific life for more [184] decades, it was very much a part of my personal life. I continued to practice daily, setting aside forty-five minutes each morning for what's called open-presence, setting aside forty-five minutes each morning for what's called open-presence, or open-monitoring, meditation. A form of vipassana, it involves being fully aware of whatever is the dominant object in the mind at a given moment, whether a bodily sensation, an emotion, a thought, or an external stimulus, but without letting it take over your consciousness. I alternate open-presence with compassion or loving-kindness meditation,in which I begin with a focus on those closest tome, wishing that they be free from suffering, and then move out in an ever-expanding radius until that wish encompasses humankind. I have found this practice largely beneficial. I live with what most people would call a stressful, overscheduled life, typically putting in seventy hours of work each week; running a lab with dozens of graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, technicians, and assistants; raising millions of dollars from private and government funders to support everyone; vying for grants; and trying to stay at the top of a competitive scientific field. I believe my ability to juggle all this, with the small amount of equanimity I can muster, is a direct effect of my meditation practice.

I didn't make a habit of talking about meditation with my scientific colleagues, figuring that it was just enough outside the mainstream to be unlikely to help my very nascent career. But all this changed dramatically in 1992. In the Spring of that year I screwed up my courage to write a letter to the Dalai Lama. I presumptuously asked the head of Tibetan Buddhism if it would be possible to study some of the expert meditators living in the hills around Dharamsala, to determine whether and how thousands of hours of meditation might change the brain's structure or function. I wasn't interested in measuring the patterns of brain activity that accompany meditation, though that might be perfectly interesting. Instead, I hoped to see how thousands and thousands of hours of meditation alter brain circuitry in a sufficiently enduring way as to be perceptible when the brain is not meditating. it would be like measuring the strength of the biceps of a bodybuilder when when he's doing curls: All the exercise enlarges the muscle,and you can measure that even when the bodybuilder is doing nothing more strenuous that lifting a latte. the yogis and lamas and monks living in the hills would be perfect for this, because they undertake meditation retreats lasting months or even years, which I suspected would have left a lasting impression on their brains. Of course, [185] perfect for science was not necessarily perfect for the meditators. They had dedicated themselves to a life of solitary contemplation. Why would they ever agree to put up with the likes of me?

I got lucky. Although the Dalai Lama had been interested in science and engineering since he was a child, looking at the moon through a telescope in the palace of Lhasa and disassembling cuckoo clocks and watches, he had recently become interested in neuroscience in particular and was intrigued by what I had proposed. He wrote back,promising to reach out to the meditating hermits and lamas in the stone huts across the Himalayan foothills and request that they cooperate with my rudimentary experiment, This, obviously, was not easy. Neither mail nor phone nor carrier pigeon was an option, and since the closest meditator was holed up in a hut ninety minutes from the end of the nearest dirt road,the Dalai Lama couldn't exactly drop in and chat during his daily perambulations. Fortunately, however, the Dalai Lama had designated a monk on his staff to serve as liaison to the lamas and monks and hermits. this monk acted like a circuit rider in the nineteenth-century American West, visiting each meditator every few weeks to bring him food and make sure he was okay (many of the meditators were quite elderly). So in the spring and summer of 1992, the emissary of the Dalai Lama brought them something unexpected: a request from His Holiness to cooperate with some strange men who would be showing up in a few months to measure electrical activity in their heads. In the end, he persuaded ten of the sixty-seven meditators to indulge us.

This was not a one-man undertaking. Traveling with me to Dharamsala that November were Cliff Saron, whom you met in chapter 2 and who was by then a scientist at the University of Wisconsin with me, and Francesco Varela, a neuroscientist at Hôpital de la Saltpêtrière in Paris. (Cliff had written such a persuasive grant proposal that we managed to wrangle $120,000 from a private foundation to support this study.) Also with us was Alan Wallace, a Buddhist scholar then at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who in 1980 had undertaken a five-month meditation retreat in these very hills after studying Tibetan Buddhism for ten years in India and Switzerland. Alan had been a student of the Dalai Lama in the early 1970s and received monastic ordination from him in 1975. We very much hoped that he would ease our acceptance by the meditators.

[186] We stayed in Kashmir Cottage, a guesthouse owned by the Dalai Lama's youngest brother,Tenzin Choegyal. T. C.,as he is affectionately known, was not only our host but also our fixer, helping us figure out the protocols involved in meeting the Dalai Lama. In return, we turned one of his rooms into an electronics warehouse. this was back in the days when computer meant not a one-pound laptop but a suitcase-size box of electronics,and the other equipment we needed to carry out the study -- electroencephalographs, lead-acid batteries, diesel generators, and video cameras -- filled five steamer trunks. Gadget-loving T. C. was in heaven.

On the second morning of our stay, after a traditional Tibetan breakfast of eggs and tea, the four of us walked down the hill and across a plaza filled with begging children, lounging cows, and blankets spread with fruits and vegetables for sale to the Dalai Lama's residence. His sprawling compound was guarded by Indian soldiers carry automatic rifles, and security was tight: We entered a two-room security shack, where we were called one by one for passport checks, bag X-rays, and hand pat-downs. Judged not to be risks, we exited security and began climbing a winding path that snaked past the dozen buildings in the compound -- library, staff quarters, administrative buildings, audience halls, private quarters. Finally, we reached the anteroom, its hard-wood walls and elegant bookcases giving it the feel of a little jewel box, where we waited to be summoned.

I was in a near panic. As I tried to formulate my opening words to the Dalai Lama, I was so nervous I couldn't come up with anything even remotely coherent. My heart was racing, I had broken into a cold sweat, and I was on the verge of a full-blown panic attack -- at which point the Dalai Lama's chief of staff, a middle-aged Tibetan Buddhist monk dressed in the ubiquitous saffron robes, walked into the anteroom and announced that it was time.

He led us into the next room,which was furnished with a large couch for visitors, a spacious chair for the Dalai Lama, a smaller chair beside it for his translator, brightly colored Tibetan thankas (embroidered silk scroll paintings) on the walls, and statues of Buddhist deities on the floor and shelves. I was the designated spokesperson for our group, but I was awash in self-doubt about what had possibly possessed me to think we might have anything at all to offer the Dalai Lama; I was sure we were wasting time.But in the fifteen or twenty seconds it took for each of us to bow in greeting and introduce [187] ourselves -- eased by the fact that the Dalai Lama already knew Alan and Francisco -- my terror and anxiety completely and utterly vanished. I felt instead a very deep sense of security and ease, suddenly confident that this was exactly where I needed to be. The words flowed out of me, and I head myself proposing that he help us study the mental abilities and brain function of individuals who have spent years training their minds, to see whether or not mental training changes the brain.

Despite all he had to deal with, from the suffering of the Tibetan people to staying in the good graces of his Indian hosts, modernizing monastic education, and tending to his own spiritual practice, somehow the Dalai Lama had found time to get up to speed on neuroscience. He was intrigued by the possibly that Western science could learn something from the men who devote their lives to mental training in the tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, and he was actually grateful that there were serious Western scientists who wanted to take this on.

And that's why we -- Cliff Saron, Alan Wallace, Francisco Varela, and I -- found ourselves making like pack mules that first morning in Dharamsala in November 1992. When we set out from Kashmir Cottage, we hadn't quite worked out the logistics of lugging all this stuff into the hills where, as I said before, the closest meditator was a ninety minute walk from the nearest road (actually, make that "road"). A Jeep took us that far, and we'd hired Sherpas to haul the seven backpacks we had stuffed with sixty pounds (each) of electronics and other gear, but as we gingerly picked our way up the mountain it occurred to me more than once that we were insane. The first time was when the "path"hugging the mountainside narrowed so much that I -- who then weighed 140 pounds dripping wet -- wished I were skinnier, the better to paste myself against the mountain and avoid plunging to my death two thousand feet below. The second was when the rocks blocking our path forced us to choose between over and around. "Over" required us to hoist ourselves over a five-foot-tall obstacle. "Around" meant placing one foot on this side of the boulder, holding on to it for dear life, reaching the other foot around to find a toehold on the other side, and praying that we could swing the rest of ourselves around to the other side rather than falling to a certain death. I don't know whether praying to every deity in the Buddhist pantheon helped, but we all survived.

[188] Finally, up ahead we spied a stone hut. That's where we found a monk I will call by the standard honorific Rinpoche 1 (we promised them all anonymity), who had been living in mostly silent retreat for ten years. One of the most experienced meditators of the ten on the Dalai Lama's list, Rinpoche 1 was in his sixties and in failing health and did not exactly embrace our mission. (Alan Wallace, whom Rinpoche 1 remembered from the months he had spent in retreat among them, translated our English into Tibetan and the lama's responses into English.) At this point we simply wanted to establish a relationship, explain our goal,and demonstrate which experiments we hoped to do. One was the Stroop test, in which the word for a color is written in ink of a different color, such as blue printed in red,and the task is to read the word without being distracted by the ink color. It is a test of concentration, of the ability to screen out distraction. But Rinpoche 1 explained all too modestly that his own meditation practice was mediocre at best (something he attributed to a gallbladder problem), and that if we wanted to learn the effects of meditation, why, we should just meditate ourselves! We had failed to take into account the fact that humility is a core value of Tibetan Buddhism, and even describing one's meditation might be construed as boastful. We left Rinpoche 1's hut without so much as an interview, let alone any EEG data.

We didn't do much better with Rinpoche 2, even though he had been of Alan Wallace's teachers. In this case, the problem was other scientists. Rinpoche 2 told us about a renowned yogi named Lobzang Tenzin, also from the hills above Dharamsala, who had traveled to Harvard Medical School for what scientists there promised would be noninvasive studies of meditation. But the Harvard researchers had drawn Lobzang's blood -- and three months after his return to Dharamsala he was dead. Rinpoche 2 was certain the scientists' meddling had killed his friend. And another thing, he told us over the course of what became a three-hour debate: It makes no sense to try to measure the mind, which is formless and nonphysical. If we did succeed in measuring anything, he assured us, it would be completely unimportant in terms of understanding the effects of meditation.

This is how it went through monks, three, four . . . through ten. One kindly advised us to pray to the Dalai Lama for success in our work. Another suggested we return in two years, by which time he might have achieved some modest success in attaining shamatha, a Sanskrit word best translated as [189] "meditative quiescence," whose goal is to block out distractions so the mind can focus on an object with clarity and stability. Others feared that undergoing our weird tests would disrupt their meditation practice. But the most consistent theme was that expressed by Rinpoche 2: Physical measurements were simply inadequate for discerning the effects of meditation on the mind. Use EEG to detect, say, the compassion that meditation has the power to cultivate? Please. By the time we reached our last monk, were 0 for 10.

Despite the scientific failure, I felt we had succeeded on another level. one of the monks had been held for many years and tortured in a Chinese prison in Tibet, finally escaping to Dharamsala. He described to us in haunting detail the moment-by-moment changes he had experienced as a result of compassion meditation, which he practiced regularly during his captivity. the sadness and despair and anger that initially filled his mind, he explained to us, gave way, a little more each day, to a feeling of compassion, including for his captors, whom he began to view as suffering from an affliction of the mind not of their own doing and so,in a sense, as being fellow sufferers. Surely I felt, this extraordinary cold teach us something about the mind and the brain.

After ten days of trekking into the hills, we finally gave upon the idea of collecting scientific data on the mediators. Before leaving Dharamsala, however, we had another audience with the Dalai Lama, telling him that our hopes of collecting the first data on the neurological effects of long-term meditation has come to naught. We explained the reasons the adepts had declined our entreaties, their suspicion of our machines, and the worrisome accounts of what had happened to other monks who cooperated with Western scientists. As the Dalai Lama sat listening to our sorry tale, he suddenly burst out, "What if you tried again with long-term practitioners -- but only those who have traveled in the West and are more familiar with Western thinking and technology?" None of the meditators in the hills had had extensive contact with the West or with science. But someone who had wouldn't suspect that electrodes might disrupt their meditation practice. Maybe we could invite such monks to laboratories in the West, rather than trying to test them in the field, and thus make use of the controlled environment there. (Bonus: no more trekking up the mountains with hundreds of pounds of equipment!) I was instantly intrigued. And when the Dalai Lama promised to put in a good word for us with some of the Buddhist adepts in his circle, I knew we were in.

[190] But he had a request of his own. He understood, he told us, that psychology research focused almost exclusively on negative emotions -- anxiety, depression, fear, and sadness. Why, he asked, couldn't scientists instead harness the tools of modern neurobiology to study virtuous qualities such as kindness and compassion? I didn't know quite how to respond. I stammered something about how most biomedical research in the West is driven by a desire to treat disease, and that this model was imported into research on emotions: Since anxiety and depression and the like are problems and even illnesses, they command the lion's share of scientific attention, whereas since love and kindness are not problems, they are largely ignored. But even as I explained this, it rang hollow to my own ears. Surely, the more we knew about positive emotions, the better chance we would have to train people to cultivate them. Yet (as I learned when I got back home), the term compassion was not even listed in the index of any major psychology textbook in those days. I vowed then and there to do what I could do to remedy this. I would do everything in my power, I told the Dalai Lama, to put compassion on the scientific map. I also vowed to be more open about my interest in meditation, to finally come out of the closet with my professional colleagues about my own meditation practice. by this time I was a full professor at the University of Wisconsin and had won several professional awards. What did I have to lose?

***

***

CHRONOLOGY (page numbers from Richardson & Begley, 2012; plus a few added references outside the book)

May 1974 - Richard & Susan Davidson; 1 1/2 month stay with Daniel & Anasuya Goleman in Kandy, Ceylon. (180)

July-August 1974 - Richard & Susan Davidson; Dalhousie, India. 10-day retreat with Goenka. (180-1)

1986 - Dalai Lama, May 27(?), 1986 – meets with Francisco Varela PhD. For more than an hour, in Paris; discuss neuroscience. DL tells Varela that when visiting West there is insufficient time for discussion, invites him to home in Dharamsala and suggests that he bring anyone he would like to. This is the origin of the Mind & Life Dialogues.

Spring 1992 - Richard Davidson letter to Dalai Lama. (184). In the spring of 1992, out of the blue, the fax machine in Richard Davidson's office at the department of psychology at the University of Wisconsin at Madison spit out a letter from Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama. [Stephen S. Hall, “Is Buddhism Good for Your Health?” New York Times, Sept. 14, 2003]

Summer 1992 - Emissary from Dalai Lama delivers requests to cooperate with Richardson to monks. (185)

November 1992 - Richard Davidson, Cliff Saron (U Wisc/Madison), Alan Wallace, Francisco Varela to Kashmir Cottage. All meditators reject scientists' requests. (187)

November (?) 1992 - Dalai Lama, in Dharamsala, makes request to Richardson: study positive emotions. (190). “When I met the Dalai Lama in 1992, he challenged me to adapt the tools of Western science, used to study fear and depression, to the study of positive qualities, like kindness and compassion. The Center for Investigating Healthy Minds is a response to that challenge and will become what we hope will be the world’s premier center for research of this kind,” says Davidson, a UW–Madison professor of psychology and psychiatry and director of the Waisman Laboratory for Brain Imaging and Behavior. [“The science of healthy minds brings Dalai Lama to UW-Madison,” W News (U of Wisconsin-Madison), Mar. 3, 2010]. [T]he term compassion was not even listed in the index of any major psychology textbook in those days. I vowed then and there to do what I could do to remedy this. I would do everything in my power, I told the Dalai Lama, to put compassion on the scientific map.(190)

April 2000 - Davidson attends Mind and Life Dialog, Dharamsala. (193)

May 2001 - Matthieu Ricard, Dalai Lama go to Madison. Ricard is tested by Richardson. (194)

2003 - MBSR - first truly randomized trial of MBSR; 2003 (202)

***

***

Comments

Post a Comment